Dr. Brenna Teigler is currently the Program Operations Manager at Cyclotron Road, a not-for-profit program designed to help hard technology innovators launch their first companies. She previously worked at the Department of Energy and as an American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Science and Technology Policy Fellow. Brenna holds a Ph.D. in Biophysics from Harvard University and a BS in physics from Rutgers. Her career has featured several “right-hand turns,” which make her story both fascinating and instructive:

Matt: Hi, Brenna. Thanks for taking the time to speak to me, I appreciate it.

Brenna: Certainly, thank you for asking.

Matt: Absolutely. Let’s dive right in. So, you’re currently Program Operations Manager at Cyclotron Road.

Brenna: Correct.

Matt: Can you tell me in your own words what Cyclotron Road is and what you do there as Program Manager?

Brenna: Yes, that sounds like a good place to start. Cyclotron Road supports hard tech innovators. Often, that’s people coming out of graduate school with some idea, maybe an early paper or a patent that may have business potential. It could be a new kind of material or a new kind of solar panel. Typically, the innovations in the program are energy focused, but we’ve also moved into the semiconductor space and clean power with some various sponsors.

These innovators are in the program for two years and they are given incubator type support. Most importantly, they are given a stipend, health insurance, and some travel funding that allows them to go all in on their venture and really figure out if there’s a business there in the technology they’ve developed. The people we bring in really want to make an impact with their science. That’s a key part of the concept. You bring in people that are motivated to change the world in some way through science and give them the resources to do that in two years. The idea is that, by the end of the program, they can raise the money they need either through grants or dilutive venture capital and be on their way to building companies.

So, that’s Cyclotron Road. What I do there is support all things related to the program that the innovators, we call them fellows, participate in. I help coordinate the fellowships from recruitment and selection to the onboarding process and all the incubator type services and programs. We have Thursday speakers and I help design who will come in and when, which also involves metrics collection. I designed a couple surveys so we can keep track of the impact and the progress our teams are making. I’m also designing the exit process: closing out what they’ve been working on at the lab, figuring out who their collaborators had been, the impact that they’ve had both on the lab ecosystem and on their companies. So, that’s what in many ways I do and it’s a collaborative job. I do a lot of work tracking deadlines and keeping people on task.

Matt: [Laughs] That’s never a challenge, is it?

Brenna: Um, it depends [Laughs]. Since we’re a startup supporting startups, there’s obviously always too much to do, so I’m in many ways there to make sure we don’t drop the essential balls.

Matt: Right. So, you mentioned Cyclotron Road is a startup, but it’s not a startup company. How would you characterize it? Like a nonprofit startup or something like that?

Brenna: Yes, it’s technically managed as a partnership between Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Activation Energy, an independent nonprofit organization. The nonprofit was formed to bring in certain kinds of capital, and to have more flexibility in the services we can provide. There are things that the national lab just is not built to do, or they would be very cumbersome because it is a national lab.

Matt: Certainly, and how many people are on the team?

Brenna: We have about ten people right now. The team has been moving from something like a basketball team, where everybody is able to do the same roles, and switch out and it’s a very collaborative nature, into more of a football team, where there are defined responsibilities and teams, like sub-teams. While we’re still collaborative, there are more specialized sub-teams. In that spirit, we’ve hired a communications specific person, we’ve hired a grant management specific person on the non-profit side. That’s part of my job as well, driving us toward more efficiency in the way we do our work to try and save everyone time.

Matt: Cool, and I guess you like it?

Brenna: I do. I like it because, we’ll get more into the background of the science I’ve done, but I still feel very connected to the science. Being at the national lab it’s just the atmosphere. Most of the people on the team have some sort of scientific background. Many people have PhDs, so it’s just the environment we’re in and a lot of the conversations we have are about the hard science. That’s especially true during the recruitment and selection process because we talk about the program being about the people. We have to bring in excellent people, but then, we also have to filter based on the technology. The technology needs to meet the impact needs of the sponsor, and it needs to make sense. We have to filter out those perpetual-motion machines. So, we get to be connected to the science and get to see what exciting things are happening out there that could have an impact.

Matt: Are you suggesting that there’s some cranks out there?

Brenna: Oh, never [Laughs].

Matt: This is probably a good segue to take it back a little bit and start exploring how you got there. You started out early on in physics as an undergraduate at Rutgers, right?

Brenna: Very correct. I went into Rutgers as a genetics major, but having done AP physics and math in high school, I was starting at Calc III in my first year of undergrad. I really realized that biology was … not engaging enough. So, that first year, midway, I switched to physics. I was already going to do a Math minor, so I wasn’t really behind in classes since I was up on the math. The switch to Physics was mostly motivated by the desire to deeply understand the mechanics of the world. I think, just the way undergraduate education is structured, the biology classes are a lot of memorization. In the more physics and math-based classes, I felt like I was really deeply learning something and that appealed to me. I did the Physics undergraduate, it was fantastic, and it seriously burnt me out on Physics in many ways. You’re doing integrals all the time and I sometimes forgot that people didn’t know what an integral was, which was very funny.

When I was winding up at the end of the undergrad during junior year, I started to think about the next step. I had already been doing a lot of research in the summer because, at Rutgers, I was at the women’s school, which is called Douglass College, and they support women in S.T.E.M. They had various scholarships you could apply for to get paid internships in research. I had already worked in the nuclear physics lab studying the magnetic moment of various nuclei and that had allowed me to go to Oak Ridge National Laboratory and participate in various research experiments where I got to babysit the accelerator overnight.

Matt: [Laughs] Many of us in the accelerator line of work have gotten that fun opportunity.

Brenna: Exactly. I really got to see that side of physics, and it is very fundamental. I could see the utility of it, but the impact on people’s day-to-day lives was too far removed from what I wanted to be dedicating my life to. I feel, throughout my career, I’ve been moving more and more to the applied side of things, both in terms of science and different roles. While I was a junior, I ended up applying to research experience for undergrads in biophysics. I was at the Nano/Bio Interface Center at the University of Pennsylvania. There I got to work on the molecular motor kinesin and myosin. Those are the little parts of your muscles that help you contract your muscles. The fun thing there was you get to actually work with those proteins and it was something that you could see.

I think that was the challenge I had with the nuclear physics, it was all very theoretical. Biophysics was different. I could actually affix those motor molecules on a piece of glass and blow in the muscle fibers and they would be fluorescent, and you could see them moving on the glass. The purpose of that was calculating the force they were exerting on those muscle fibers. You would look at the velocity and use that to infer a lot of the mechanics and the biophysics of how your muscles work, and how these different types of mechanisms operate together to create a functioning muscle.

I found that to be a great experience and I could see how it’s directly applicable to people’s lives. So, when I was thinking about graduate school, I was drawn to biophysics because really that was the experience I had had. I feel if energy had been part of the picture, I probably would have also been drawn to cleantech and those other applicable applied physics-y fields at that point. But it just wasn’t …

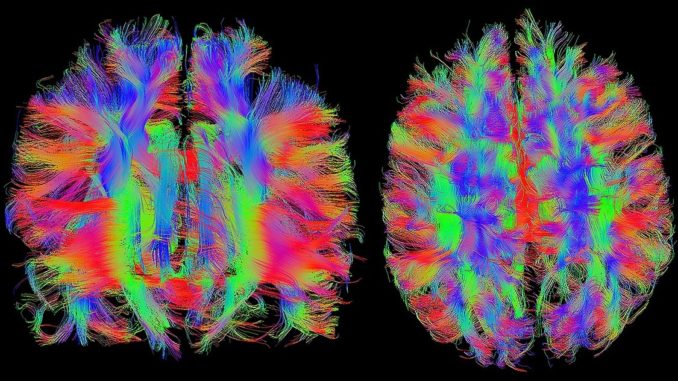

I was also sharing a campus with the biology school at Rutgers and there was just a lot of subtle hints of biology in the air. The brain was really cool at that point; it was a few years before Obama’s BRAIN Initiative. So, for some reason, I was like, neuroscience is where it’s at and ended up applying to graduate schools for biophysics but wanting to work in a neuroscience lab.

Matt: So, you kind of got caught up in the moment a little bit?

Brenna: I did. I got caught up in the wave of neuroscience that was happening. The funny thing there is I didn’t know what it meant to do research in neuroscience. The fun thing about graduate school interviews was that I got to speak with all the different researchers and really hone in the scales. In neuroscience, you have the whole brain system at the top, so you can work at the full brain level, which is the imaging, like the fMRI. You can also look at the systems level, how the different cellular networks talk to each other. You can work at the cellular level. Or, you can go sub-cellular to the different ion channels.

I explored all the different scales and decided I liked the systems level, in part because you could really understand some of the physics involved. That’s also true of the ion channel levels, but it felt like one of the frontiers was really understanding the different circuits in the brain and how those were creating various behaviors and outputs. It’s an input-output function type process. I was really drawn to that systems-level neuroscience.

Matt: I see. You had gotten, like you said, caught up in the excitement of the topic, but as you were making your graduate school choice, did you have any particular vision for your future career or what you were going to do with that Ph.D.?

Brenna: At that point, when I was just starting to interview, I didn’t. I was starting to think about it, and the funny thing is that it came up at my last interview for Harvard. That’s where I ended up going to grad school, in their biophysics program. I was talking to a biophysics professor and he told me that if I was not 100% driven in my soul to answer the scientific questions in an academic way, those core fundamental questions of science, rather than the applied science or the more policy-oriented or the communication-oriented aspects of science, then I should do something else besides be an academic.

In my mind, I had been thinking about the academic route because I feel like that’s what we’re trained to do, to get on that academic path. So, at that moment, before I had even started graduate school, I decided, “Okay, I’m not going to be an academic scientist.” Yet, I’m going to graduate school where you’re essentially trained to be an academic scientist. So, I somewhat thought of graduate school as an entry-level position to explore scientific careers.

Matt: Okay, really?

Brenna: Yeah, I feel like that served me very well.

Matt: So, you went in, day one, thinking, “No professorship for me, I’m going to do something else with this?”

Brenna: Exactly.

Matt: Okay, wow.

Brenna: I still loved the science and I wanted to do something with that, but not take that traditional academic pathway. I guess I was open to it, maybe if I decided that that really was what was calling me, then sure, but that I was going intentionally for other possibilities.

Matt: How did going in with that attitude affect how you spent your six years at Harvard?

Brenna: I spent a lot of time doing extra-curricular activities.

Matt: Like what?

Brenna: At least for the first couple of years I spent the nine-to-five in the lab, very regular hours. Outside of that I was part of a lot of student groups. I was initially in the Harvard Science Policy Group, which was a newer student group and I was essentially on the executive team to try to get it going. I participated in a lot of volunteer events through the Dudley House, which was the sort of “graduate home.” Harvard has their various houses, and the Dudley House was the graduate house. I participated in a lot of events that they put on, particularly career-oriented ones. I spent a fair amount of time at the career services office talking to their counselor about various pathways. I also explored options at the Harvard Medical School since my biophysics program was technically housed over at the medical school in Boston and not in Cambridge.

I also had friends in various groups that I kept tabs on. You obviously can’t do everything. One friend was really into consulting and she thought that would be her path. So, I kept tabs on what the consulting pathway looked like through her. Another friend was in the Harvard Business Club and I kept tabs on what kind of events she was going to and the people she was connecting with. I had another friend in the Medical Devices Group, and he was making certain connections there. I mostly dove into the policy world. I was also part of a science policy group at the medical school that was just getting started. That connected me with groups like the Union of Concerned Scientists and some of those more … I guess some people would call them lobbying or activism, but groups interested in the impact that science has on society.

A big thing I did was that I technically got a minor during my Ph.D. It was a new program they had started where you could get a secondary field if you took a certain number of credits. So, I took a lot of classes at the Harvard Kennedy School, which is their government and policy school and I got a minor in Science, Technology, and Society.

Matt: I have never heard of a Ph.D. minor before, that’s interesting.

Brenna: Yes. I think they still have that program going and I think it was really nice. I mean, you are paying anyway, you might as well have a reason to take some of these other extra classes. I was interested in taking those classes anyway and it justified me taking the time.

Matt: Interesting. I have to ask, because I know a lot of people might be thinking at this point about your advisor’s attitude toward all this. There’s often a lot of pressure in graduate school to be in the lab much more than the nine-to-five. Did you take flak from your professor for any of this, or was it tough going at some points?

Brenna: That’s a good question. I feel like you’re still getting your feet under you the first couple of years of graduate school, so it’s okay if you take a little longer to get rolling. In part, I selected my professor because he was a bit more relaxed. He had tenure for at least ten years at that point. This isn’t the only reason I chose him, but he wasn’t trying to get tenure. I wasn’t pushed the way some younger professors push their graduate students to make progress on a fast time scale. I did eventually have to make a switch in the way I approached graduate school in order to actually graduate because, at the pace I was going, it would never happen. So, after I completed the first two years, and passed my qualifying exam, that started the switch into a more intense load of research at the lab.

What really solidified the change was my boss taking a job at Caltech. I actually moved with him, in the middle of my Ph.D., and helped him set up the lab out in California. At that point, he actually said to me, because I wasn’t working as much and was still adjusting a bit, “You either work hard and get this done or just don’t come back.” So, I was like, “Well, I think it’s time for me to get this done.”

Matt: I see. You got an ultimatum, huh?

Brenna: I did. I did. I think that’s what I needed, and he knew that. While I was still involved in some extra-curricular groups at Caltech, it was on a much smaller scale.

Matt: I see. You took a hardcore little “vacation” to get your thesis done?

Brenna: Exactly. Sometimes you just gotta dive into the science.

Matt: I pulled your thesis title and I’m going to read it here because it’s pretty cool: Predicting the Electrophysiological Responses of Murine Alpha Retinal Ganglion Cells to Artificial and Natural Visual Stimuli.

Brenna: Mm-hmm, that’s it.

Matt: I’m not gonna try to say that three times fast.

Brenna: Yeah, it’s a thesis title through and through.

Matt: Now, as you were wrapping that up, where were you with your career vision? We already talked about how your career focus was outside academia from the beginning and you did all this extracurricular stuff. After hitting the science hard for a few years to finish, you’re wrapping up and what were you thinking career-wise?

Brenna: I briefly considered staying, actually doing science, and going into industry. I selected my professor mostly because he was like me. He got a Ph.D. in physics and then switched to the biology. He brought his physics with him and took a really physics-like and quantitative approach to the biology. That’s what I wanted to do in my Ph.D. While I liked that environment, I realized I wasn’t a biologist, so I didn’t want to stay on the neuroscience route. I wasn’t into tinkering, building, and fixing things. So, I felt like the experimental physics path wasn’t a good fit for me either and I didn’t want to just do theory. I liked engaging with people, and I didn’t want to only be in the lab.

All those things combined with my view that we needed more smart people in Washington. I felt we needed more scientific decision-making in DC and I decided that was the place for me. I saw a pathway for fairly immediate impact using science and scientific thinking on people’s lives when it comes to policy and science policy in particular. As I was wrapping up my Ph.D., I was really aiming for the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Science Policy Fellowship.

It is an arduous process to apply, so I got my professor onboard. You had to have your Ph.D. in hand before you could actually apply and then the application only happens in November. If you actually get the fellowship, you don’t start until the following September. I was able to finish my Ph.D. in October, apply in November, and then finish up a lot of the work I had in the lab as short post-doc before I actually started in September.

Matt: I see. You did one fellowship and then another at the AAAS, is that right?

Brenna: Good question, the fellowship is designed to be a one-year program that’s a good fit for people who want to take a one-year sabbatical from academia. The experience helps them to understand the grant-making process and what people are looking for when it comes to both policy and the projects that actually get funded. They can easily do that and then go back to do the science; you’re not out of touch. AAAS also understands that, in a year, you might not get much done, so they allow you to extend for a second year. The way it worked out for me, I decided to pivot to clean energy and energy challenges. I don’t know if you’re noticing throughout my career, but I’ve made a lot of right-hand turns. [Laughs]

Matt: [Laughs] I did pick up on that, yes.

Brenna: Yeah, I guess there’s been a trend of including science in what I do, along with a preference for more quantitative type work. I’ve changed what I’ve actually done and the field in which I’ve done it quite a lot.

As I was wrapping up at Caltech, the water-energy nexus is very clear out in the southwest and I was exposed to a lot of different challenges. The solar boom was definitely happening out there in California. For the first time, I somehow realized that this energy challenge is the huge challenge of our time. I was going to DC to have an impact, and if I really wanted to have an impact on what was important to our generation, energy was the thing to work on.

I was fortunate to get a position at the Department of Energy and I ended up doing two years in two different offices. The first year I was in the Clean Energy Manufacturing Initiative and that was, in many ways, a political initiative started by the assistant secretary at the time. When we were coming up on the election, it was clear that since it was more politically oriented, it wouldn’t make sense to continue that work so that initiative was winding down a bit. I jumped to a related office called the Technology to Market Office. I took most of the projects I was working on with me but under a new umbrella.

Matt: I see. That experience with the AAAS, and government at the DoE, didn’t tempt you to stay in Washington?

Brenna: Well, I honestly thought about it. I think I would have liked, in some ways, staying on as a federal employee at the Department of Energy. The challenge, in some sense, was that the election happened and hiring froze because there was so much uncertainty.

Matt: Sure.

Brenna: In the end, that turned out to be a good thing for me because I realized that what I was really doing at the Department of Energy was enabling people to do cool things. A job at the Department of Energy, in many ways, is giving out money. We convene people and we give out money. When you convene, you’re making a strategy for how you should spend that money. So, while there’s a lot of power and excitement in that whole process, I wanted to be more in the weeds. I wanted to be one of those people doing the cool things or at least closer to that, instead of only being the one that was enabling the cool stuff. In that sense, the private sector, at least moving closer to that, was a good next step for me.

Matt: I see. You wanted to get a little more high-touch with the process.

Brenna: Yes, and the funny thing is that at Cyclotron Road I’m still not in one of these companies making an impact through science. I’m still, in many ways, enabling people to do the cool stuff, but I am a step closer to that and I think it’s kind of a subtle distinction, but, it’s a good fit for me. It’s like finding that point in the spectrum of how deep in the weeds you want to be.

Matt: You’re also gaining more experience and maybe there’s another right-hand turn for you in there a few years down the line, huh?

Brenna: Maybe, or maybe I take a step further and I join one of those companies.

Matt: There you go. I’m curious, because I get questions about this a lot. On the journey you’ve taken, what do you see as the key advantages of having completed a PhD in Physics, or in your case Biophysics, as opposed to stopping, at say, a Master’s?

Brenna: Sure, sure. I think there are a couple benefits. First, I think when you go through the process of completing a Ph.D., you really have to learn how to finish something and that’s in part what I meant when I talked about moving to Caltech and my boss giving me an ultimatum. I really had to internalize that, “This is my project. I need to drive it to completion; no one’s going to do it but me.” So, while I always was one to take initiative, it’s a different level of initiative and digging in to get something done that the Ph.D. teaches you how to do. I think that’s an extremely transferable skill that I would not have had as deeply without the Ph.D.

In my current role, it helps me to have a Ph.D. because of the lived experience. Most of the founders in the program also have doctorates. I can go to them and be like, “I’m a Ph.D., I had that same exact experience.” So, it’s like a club in some ways, and you can bond on that level.

Matt: Yeah, I guess if you’re going to call yourself a scientist, a Ph.D. is kind of like the union card.

Brenna: Exactly. I think there are a bunch of other skills you also gain. I think that not all of these skills are common, the Ph.D. experience depends on your lab for better or worse, but I really learned presentation skills. We had weekly team meetings where I had to present quarterly on the progress of my work. I had to learn how to both design and give an effective presentation. On the weekly level, I met with my P.I. and I had to learn how to run an effective meeting, how to go into that meeting with an agenda and something I wanted out of it, so I didn’t waste my time or his. Those are skills I definitely use today, and I would use in any job.

Matt: It sounds like you may have had a better Ph.D. experience than most in that context.

Brenna: Yes. That’s what I mean that it unfortunately varies, and it depends in many ways on your boss, but you just don’t learn those same skills in classes during the Master’s period.

Matt: Absolutely not. I think someone might very well learn the meeting and presentation skills you talked about working a regular job, but it is a lot harder to have that experience of really, personally completing a large-scale project. That’s almost unique to the Ph.D. and definitely a big deal.

Brenna: I definitely agree.

Matt: OK, I always like to ask one specific wrap-up question. A big part of the motivation for doing these interviews is to provide guidance for the folks coming up behind us who are now undergrads or graduate students. If you had one key piece of career advice that you could give those folks, what would it be?

Brenna: This is pretty specific, but, I’ll say don’t do a postdoc without a plan. Since many of us go into a Ph.D. program with that academic track in mind, it can be very easy to graduate and then immediately take a postdoc because that’s what everybody does. If a postdoc is not in your critical path for your career, take a hard look at where it will get you before accepting it. There are so many other options out there for you as a Ph.D., don’t feel like that’s your only option.

Matt: Because it’s all too easy to get on that postdoc treadmill, right?

Brenna: Exactly. I know it’s not all about money, but you generally get paid less as a postdoc than if you go into something else. You also won’t necessarily gain additional skills during that postdoc, or necessarily get paid more when you finish it than if you had just gone straight to another sort of job.

Matt: Absolutely. No, it’s not all about money, but money’s always a factor. That’s especially true when you’ve been making very little in graduate school and you’re almost 30 by the time you finish.

Brenna: Mm-hmm. Yeah, so make sure when you’re going into a postdoc, you have a good reason for it.

Matt: Okay. I think that’s fantastic advice, Brenna. This has been a great interview, and I really appreciate it.

Brenna: It was a lot of fun. I’m glad you asked.